We have spoken often of Guanyin (in Sanskrit, Avalokiteshvara, Japanese, Kannon), the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion--most recently in "The Main Courtyard" in Episode 148, and "Twelve Tales of Guanyin" in Episodes 136 and 137.

I have previously shared with you in this newsletter dozens of pictures of this most popular of Buddhist figures--arguably more popular among the "folk" than the historical Buddha himself.

But in all this time, I don't think we've ever taken a close look at the iconography of this fascinating figure--the symbols used to highlight various aspects of his/her character.

You may be familiar with some of the iconography of Christianity: A brown-robed saint with a bird on his shoulder? Why, that's Saint Francis! Another monk, this one with a broom and a dog? Saint Martin de Porres. And so it goes.

But when we cross cultures, things get a bit harder. That's because, in the examples given, you need to know something of the saint's story to appreciate the symbols.

But anyone can recognize that halo = holy, or blood = suffering. These symbols are universal, untethered from specific narratives.

Keep this in mind as you read the twelve characteristics below. In a few cases, there may be a backstory; but in most cases, there is a logic to the symbols that transcends specific tales. It helps, in any case, to know that Guanyin's primary purpose is the practice of compassion.

So let's pause from our labors to look at some pictures and appreciate what the sculptors can teach us.

Note: As you view the example pictures, look not only for the characteristic described but for some of the others as well. It may be worthwhile to go back and look at the images one by one--with the list of 12 characteristics in mind--when you're finished.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 1: Gender Fluidity

As we discussed when we met "Guanyin in the Drum Tower" in Episode 148, many images of Guanyin are noticeably feminine in appearance, though the figure never has breasts--in fact to the contrary, the chest is often bared and decidedly masculine.

What's up with that?

Well, there's the historical reason: Avalokiteshvara in India was invariably male, and when he came to China, took on a more feminine appearance. As I explained in Episode 148, this may be because "compassion was regarded as a more-or-less 'feminine' trait."

Or it could be that the imagery was influenced by Mazu (see Episode 142); or the ancient Daoist "Queen Mother of the West" (Xiwangmu); or even--much later--the statues of the Virgin Mary introduced to China by the Portuguese in the early 16th century.

But again, as mentioned in Episode 148, the Bodhisattva can take many forms, depending on the needs of those whom he/she will aid. "For example," I wrote there:

if a child is nearing enlightenment, the Bodhisattva may appear as a child to help that child along; if the candidate is a monk, Guanyin appears as a monk; she's a bodyguard for those about to be attacked; a water-bearer for those threatened by fire; a teacher for those who are confused. Whatever the cause of suffering may be, Guanyin can counter it.

She may also appear as a deva (a god), a naga (a serpent), a yaksha (a nature spirit), a gandharva (a celestial musician), an ashura (a belligerent titan), a garuda (a giant bird, like a roc), or many other beings, natural or supernatural...

So when I see this sexually ambiguous figure, I am reminded that not just her gender is fluid, but that even her very species can shift to allow her to bring help to the suffering.

(You'll notice that I tend to use feminine pronouns for Guanyin. Masculine pronouns would be just as valid, but I feel more comfortable with seeing her as female.)

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 2: A Thousand Arms

I have to be honest: seeing a figure with way too many arms used to freak me completely out.

But with Guanyin it makes perfect sense.

The many arms represent the many ways in which she can help those who need it. To highlight the point, the hands in some figures contain various tools and other objects (like cash!) that may be used to help, in addition to the supernumerary arms.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 3: Eleven Heads

Guanyin is often depicted not only with too many arms, but with too many heads as well--if the number exceeds the usual one, it's likely to be eleven.

The symbolism? It's so she can "here the cries of the world" (the meaning of her name) and see problems as well.

One explanation of the number eleven is that it's the ten stages of enlightenment (as described in the Dashabhumika or "Ten Stages" Sutra, plus one--in the topmost position--for Amitabha (see Characteristic 4, next).

Another explanation of the number is that Guanyin is seeking to offer aid in the ten directions (the usual four, plus the ones in between, plus the apex and nadir--above and below). The "ten directions" (or sides) are a common idea in East Asia; the film you may know as House of Flying Daggers is called in Chinese "Ambush from Ten Sides." Amitabha is added to the top once again to make eleven.

The eleven may be arranged in many configurations: sometimes three groups of three plus two on top; sometimes like ten lollipops sticking out in a circular display, plus the Amitabha on top; and several others.

It is not uncommon to find figures of Guanyin with eleven heads and a thousand arms (as in Images 3, 4, and 7), able to see, hear, and help in myriad ways.

- - - - - - - -

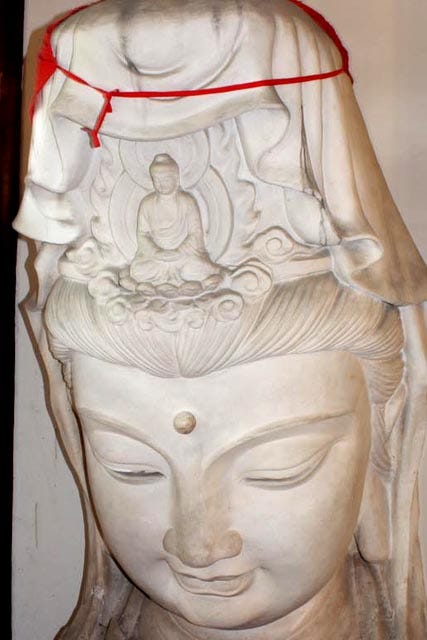

Characteristic 4: Amitabha in the Tiara

As already mentioned, Guanyin is almost always shown with a figure of Amitabha in her tiara (or atop the arrangement of the many heads if it's an Eleven-Headed Guanyin statue). When faced with a figure of an unidentified Bodhisattva, the image of Amitabha in the headdress is a dead giveaway.

But why is Amitabha there?

The Beihua Sutra tells us that in a previous life Avalokiteshvara had been a crown prince, and--just as the son became a Bodhisattva, his father the king became the Buddha Amitabha. So Avalokiteshvara owes his power to that Buddha, and is considered an emanation of him.

The figure of Amitabha may be standing or seated, sort of blobby or shown in great detail. But no matter how he is portrayed, he is like both a signpost and a battery, identifying the figure as Guanyin and giving her power.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 5: The "Third Eye"

The earliest Buddhist scriptures included a list of the "Thirty-two Characteristics of a Great Man," physical marks by which a Buddha (or a Universal King) could be recognized. Some of these are quite outlandish: wheels imprinted on the bottom of his feet; webbed fingers and toes; his penis in a sheath like a horse's; forty teeth, a tongue that can touch his forehead; and the protuberance commonly seen on the top of a Buddha's head--which we'll mention again in a minute.

I bring this up because one of the marks is a tuft of hair between the eyebrows which has evolved in the iconography into a "button" (actually a jewel) in the forehead, just where we might expect to see a "third eye."

Let's switch paradigms for a second. In Indian thought, there are seven "power centers" along the spine, called chakras. In common thought, these are at the levels of:

the anus, representing food (and in modern times the money we use to buy it);

the genitals, representing sex;

the navel, representing power (think of the "solar plexus");

the heart, representing balance;

the throat, representing religious practice;

the forehead, representing spiritual perception (the "third eye"); and

the top of the head, representing the connection to the Transcendent (a little like an antenna).

The first three chakras embody the lower motivations that humankind shares with animals.

The heart is the balance point between the lower three and the upper three.

The three "higher" (more spiritual) chakras, again, are:

the fifth chakra, at the level of the throat, which is used in chanting, and thus is considered "practice."

the sixth chakra, represented by a jewel in the forehead, which replaces the tuft of hair mentioned in the earliest scriptures; see Images 6, 8, 12, 13, and 14. This chakra has come to be understood as essential to spiritual perception--thus, its designation as a "third eye"--and is sometimes shown explicitly, as in Image 7, instead of symbolically. The third eye represents seeing not just with the eyes, but with the "heart," with the spiritual faculties.

the seventh chakra, indicated by the "bump" (ushnisha) on the heads of Buddhas. This may explain the presence of Amitabha atop Avalokiteshvara's head, a symbol of her connection with a cosmic Buddha.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 6: The Vase

Let's move on from the Bodhisattva's head to her hands.

It is extremely common to see Guanyin holding a vase. This is sometimes held upright, but at other times is tipped downward, and the sculptor may even include a stream of liquid pouring out of it.

What could this liquid be? Common answers are water ("Water is Life"; we can't live long without it), or a sort of nectar or ambrosia. In any case, it's a liquid embodiment of compassion. It can be whatever is needed by the sufferer.

The upright vase speaks more of potential; the tipped one is compassion in action.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 7: The Lotus

Lotus flowers--real ones, and decorative arts--are found throughout many Buddhist temples.

Their meaning is simple and profound: the lotus is rooted in the mud; it grows up through the water; and emerges into the air. So we are born in the "muck" of the world; we develop through our lives; and we emerge transcendent into a new condition (in many of the world's spiritual traditions).

Guanyin (like Amitabha) is often seen holding a lotus. If it's a bud, it--like the upright vase--indicates potential; if it's in full bloom, it is fulfillment. See Image 5 for a Guanyin holding a single vase containing lotuses in three stages of development.

You may also notice that Guanyin is sometimes seated on a "lotus throne," with all of the same implications as the lotus flower. We'll talk about one more type of "seat" before we finish up.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 8: The Gestures

There is a wide variety of gestures, called in Sanskrit mudras. The mudras displayed by statues of the historic Buddha are fairly well-known and codified.

But the ones used by Bodhisattvas vary from sect to sect, from master to master. Many carry esoteric meanings. One of the most common, however, is the middle finger touching the thumb (like "okay" with the wrong finger), and the index, ring, and little fingers extended. This is said (by some) to represent a lotus.

It is often raised, but in some cases held horizontally or even lowered. If it is indeed a lotus, it would represent the meanings described in Characteristic 7.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 9: The Willow Branch

Guanyin is often seen holding a piece of greenery that resembles a sprig from a willow tree. This may indicate use in a kind of asperges rite, sprinkling the same substances (water, ambrosia, etc.) as are found in the vase. It is not a flail!

Willows are said to be resilient (they bend but don't break); and the tree's "willowy" form reflects the grace often seen in standing statues of Guanyin.

I have found another peculiar meaning to the willow I see in Guanyin's hand. In 1897, a German company isolated acetylsalicylic acid, a substance derived from the salicin found in willow bark that seemed to help with headaches. The company's name was Bayer, and the product was named aspirin--though the use of willow for reduction of fever and pain had been around since ancient Sumer.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 10: The Jewel

In the section of Episode 148 called "Guanyin's Attendants," I told of how the granddaughter of the Dragon King of the Eastern Ocean brought Guanyin a jewel (or pearl). This gift was sent by the King to thank the Bodhisattva for saving his Third Son, the girl's uncle. The jewel was said to emit light, which allowed Guanyin to read scriptures at night.

So, sometimes, Guanyin is seen holding something about the size of a marble, said to be the Dragon King's gift.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 11: Attendants

Let's take a look now at things that can be seen near the figure of the Bodhisattva.

Often--though not always--Guanyin is accompanied by two attendants, a girl and a boy. I have told their stories at length in "Guanyin's Attendants." Here let me just reiterate that they represent pairs of opposites--female vs. male, lay vs. monk, and so on--the yin and yang that are reconciled in the figure of this versatile Bodhisattva.

- - - - - - - -

Characteristic 12: The Qilin

Finally we come to Guanyin's vahana or "vehicle." This is the mythical animal on which a Bodhisattva sits.

Puxian (Skt Samantabhadra) sits on a six-tusked elephant, representing the taming of the mind.

Wenshu (Manjushri) sits on a lion, whose roar represents the Buddha's teachings.

Dizang (Kshitigarbha) (when seated--he often stands) sits on a diting who was once his dog, representing his vow to save all beings (including his own mother) from the Six Hells.

And Guanyin sits on a qilin. Because it may have a single horn (though sometimes it has two), it has been compared to a unicorn. (But be careful: Dizang's diting also has a horn!) It represents benevolence, bravery, and virtue, all traits of the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

The qilin is a fairly common figure in China, and is counted among more famous figures like the dragon, the phoenix, and the turtle.

But some beer drinkers will recognize it from the label on a bottle of Kirin (the Chinese pronunciation of qilin) beer.

And that brings us to the end of this quick survey of Guanyin's iconography. We have taken a look at some of the most common characteristics; there are many others, including Guanyin with a Horse's Head; Guanyin with a Child: and many, many more.

And that's that! I hope you enjoyed getting to know this important figure a little better. Until next time, may you and your loved ones and all sentient beings be well and happy.

Adios, Amigos!

GET MORE:

Find this and all past issues of the Newsletter online at Substack.

If you have any problems reading the Newsletter , please write to me at TheTempleGuy@GMail.com, and I'll help you in any way I can!

Are there stories attached to the qilin? I think of Guanyin with a dragon and with a parrot but I never saw that qilin before — it’s a cool beast!