Ep. 131: The Four Sights and the Great Departure

How the Buddha-to-be came to leave the palace in search of Enlightenment

Here is the monthly story available FREE to all subscribers. Enjoy!

Prince Siddhartha was, frankly, bored.

Yes, he had things good, extremely good. Perhaps none had it better. His father, King Shuddhodana, had provided him with everything a young man could ask for. Every year, he moved between three palaces, one for each of the three seasons: the cool season, the hot season, and the rainy season. Each palace was sumptuously furnished, with healthy young attendants to serve the young Prince and his wife. Parks and gardens stretched around the palaces, where he could sit, stroll, fish in the lakes, or engage in the sports at which he excelled: riding, hawking, archery, wrestling, and others. He had no end of entertainments, and could pursue whatever his heart desired.

Almost. There was one thing he was not allowed: he could not leave the palaces and go out among the people. He felt like a prisoner.

At last, one day, he approached the King.

"Royal sir," he said, "Is it not true that I am meant someday to take your place and rule Kapilavastu?"

The young man could not know how pleased his father was at the question. After the boy's birth, all the wise men had predicted that he would become a king like his father--except for one, who suggested that he might instead become a spiritual leader. It was to keep his son on the path to leadership, not distracted by the suffering of the human condition, that the King had sheltered him so.

"Yes, my son," the King replied to Siddhartha's question. "That is certainly my hope."

"But how can I do so, Father, when I do not even know how our people live?"

It was as the King had feared: in trying to keep his son from becoming an ascetic, he had failed to prepare him to be a king!

"What do you propose, Siddhartha?" his father asked. He trusted the lad's wisdom, and hoped he might have a solution.

"Why don't we ask my man Channa," the Prince said, "to take me out into the city on a royal visit?"

Excellent! The King knew he could trust Channa to shelter the young man from negative influences, and yet give him just enough exposure to satisfy his curiosity.

"Well done, my boy!" said the King heartily. "It shall be done. Send Channa to me at once."

And so the King counseled Channa on his wishes for the Prince, and also arranged through his ministers for the city to put on a display. "Remember, Channa," the King said in a final admonition, "stick closely to the route that we have agreed on, that the Prince might be exposed only to the best our people have to offer."

"It shall be done, My King," the man replied.

The First Sight

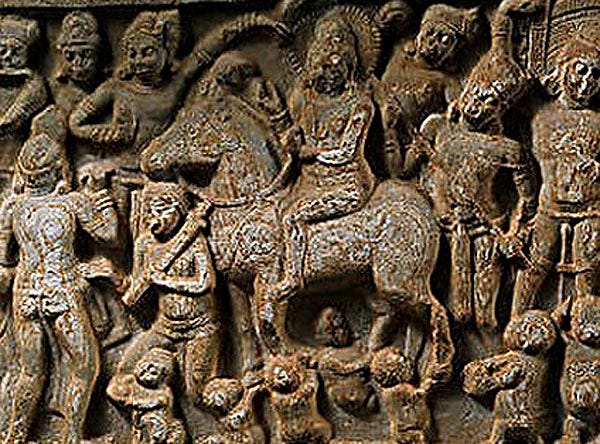

The great day arrived. Filled with anticipation, the Prince mounted his chariot, with Channa driving.

The palace gates were opened and immediately a roar went up from the crowd of citizens lining the streets. Garlands were strung overhead; flags waved from the buildings; and everything was freshly cleaned and painted. It was beautiful!

But as luck--or the gods--would have it, just as the procession turned a corner, a bent-over person, leaning on a stick, broke through the crowds and feebly crossed the street.

"Stop, Channa!" ordered the Prince, as a hush fell on the cheering crowd. "What is wrong with that man?"

Torn between the King's command and his honest nature, Channa replied at last, "That man suffers only from old age, My Prince."

"Old age? What is that?"

"Well, Prince Siddhartha, remember your last birthday party, when another year was added to your age?"

"Of course, Channa, how could I forget? My whole family was there, and musicians, and dancing girls, and we had sports competitions."

"And the year before that?"

"The same," the Prince replied. "I see: with each birthday I get a little older."

"True," Channa replied, "but actually, My Lord, we get older with each day, each hour, each minute. That man we see has lived many more years than you, or even your father."

"But why does he look like that? His hair is a dull gray color, not jet black like ours. His face is wrinkled like old fruit. And his teeth! Does he even have any? He walks as one who cannot see, like we do in the game we play with blindfolds. And he clutches that stick with both hands as though he were afraid of falling. Was he born like this?"

"No, My Prince. When he was younger he was very much like you and me." And after he thought a moment, he went on. "My Lord, do you not remember the chariot races we had with your cousins last year?"

"Oh, yes, Channa! That was some fun!" the Prince replied, brightening up a bit.

"And remember when a wheel came off of one of the chariots?" Channa asked.

"Yes! I was barely able to dodge it! Still," the lad went on, a mischievous look in his eye, "I managed to win."

"As you always do, My Prince. But why do you think that wheel came off?"

"Oh, that made me a little angry," said the Prince, frowning. "Devadatta had not maintained his chariot properly, putting the rest of us in danger."

"And why do we need to maintain chariots, My Prince?" Channa asked.

"Because, Channa," Siddhartha replied, "if we did not, they would fall apart from neglect."

"That is true, Prince Siddhartha. In fact, all things deteriorate with time--even the human body."

"Channa!" the lad exclaimed. "Do you mean that will happen to me!"

"Yes, Your Grace," Channa replied gently. "If you are fortunate to live for many years, in time you will become such as this man, suffering from the effects of old age."

Pensively, the Prince said, "Channa, please turn the chariot around and take me home. I no longer feel the joyful spirit of this quest. I must think more about this."

"As you wish, My Prince," Channa said, not a little worried about what the King might think.

The Second Sight

Upon returning home, Prince Siddhartha had little appetite and, though he retired early, was not able to get any rest. His mind kept returning to the old man on the street. This would happen to everyone who lived long! His father, his beloved mother, all his friends, even his wife Yashodhara! How had he reached the age of 29 without knowing about such things? Unbeknownst to him, it was a testament to the care his father had lavished on him. The King had been exacting in ensuring that only young and healthy people surrounded the Prince.

Upon rising the next morning, the Prince called Channa to him and again requested to go out.

"But My Prince," Channa said, "how can I do so without your father's permission?" He was also thinking that the city would be caught unawares.

"As you say, Channa, I am your prince, and I wish it to be so."

Reluctantly, Channa hitched Kanthaka, the Prince's great white stallion, to the chariot, and they set out again.

This time there were no "Huzzahs," no waving happy people. The garlands had begun to wilt, the flags were slightly soiled, and the people were going about their business. He saw blacksmiths and other craftsmen working, sweat shining on their skin. Merchants were haggling loudly with customers. Bakers were busy making bread and sweets, flour dusting their faces. The Prince had never thought before that behind all the good things in his life there was human effort.

As they drove again through the streets, they came across a man lying by the side of the road, a bowl for alms resting next to him. The man gripped his belly with both hands. His skin was plagued by open sores. His tongue lolled out of his mouth, and his eyes bulged in pain.

"Good sirs!" he cried out. "Won't you spare something for a man who cannot work?"

"Channa," the Prince inquired again. "What is wrong with this man? Why does he look so uncomfortable, and why cannot he work to support himself?"

"That man, My Lord," Channa said, "is suffering from a sickness which has no cure."

The worried Prince asked, "Is this unique? Or are there others like him?"

"There are others with this sickness," Channa answered carefully. "But there are many, many more who suffer in other ways. Hundreds of ailments are known to affect humans, and many more for animals."

"But this is terrible!" the Prince exclaimed. "Why did I not know about this?"

"Have you not noticed, My Lord," the troubled man said, "that sometimes one of the people who serve you is absent from his or her post?"

"Oh, yes," said the Prince. "Just last week the cook was unable to come to work, but no one could tell me why. My father's cook had to prepare my meals."

"I remember," replied Channa. "That man was sick. Nothing serious, but he was ill enough that he had to take some time off. Besides, it is not good for a sick person to prepare food, as others might become ill because of him."

"This can happen so easily to anyone? At any time?"

"Yes, Prince Siddhartha. You have been wonderfully healthy, but this could even happen to you, without warning."

Again, Siddhartha asked to return home before the tour was completed, and again he had a restless night.

The Third Sight

The next morning, he asked to go out again. Channa had duly reported everything to King Shuddhodana, who had reluctantly given the man permission to fulfill the Prince's whims. "Perhaps," he reasoned, "this will make him a more sympathetic king someday." He could not know the radical effect it was having on the young man already.

Again Siddhartha and Channa set out, and this time they chanced to see a funeral procession, although some attribute these sightings not to "chance," but to the intervention of the gods. (Thus, the "Four Sights" are sometimes called the "Four Heavenly Messengers.")

A crowd of people was coming toward them. Women were weeping aloud, and men looking down at the ground. Behind them came a small group of men carrying a kind of wooden plank, and on it was what appeared to be a man, covered with a white sheet. Yet he never moved or cried out, even as the men jostled the plank to set it on a pile of wood.

Then, to his astonishment, the Prince saw the men set fire to the wood, with the man on it!

"Channa! What are they doing to that man?" he asked anxiously. "Will that not cause him pain?"

"No, My Prince," Channa said, his voice gentle once again. "That man is beyond pain. You see, he has died."

"Died?" the Prince exclaimed. "Old age, sickness, and now this? I suppose this also happens to all?"

Channa trod carefully as he answered. "Does the Prince not know that Prajapati, whom he calls 'Mother,' is not the woman who gave birth to him?"

"Ah, yes, Channa, my father has told me something about this. Please remind me?"

"Just seven days after you were born," Channa explained, "your birth mother, Queen Maya, passed away, and--"

"'Passed away'?" the Prince interrupted. "Do you mean she died?"

"Yes, My Prince."

"So even queens can die? And kings?" He was thinking of his own dear father.

"Yes, Lord. Death will come to all, the richest and the poorest, and to everything that lives--sooner or later."

"Even trees, Channa? And elephants?"

Channa smiled sadly. "Yes, Prince Siddhartha. Even trees and elephants."

And still again the Prince asked to be taken home to contemplate this new problem.

The Fourth Sight

One more time, the Prince, with his charioteer and mentor, entered the city. "I hope, Channa," he said, "that we will see nothing terrible this time. My heart is already breaking over the events of the last three days."

Channa replied, "I understand, My Prince, but what will be will be."

As they neared a large park-like area planted with ancient trees, Siddhartha asked Channa to stop and tether Kanthaka so they could get out and stretch their legs.

As they walked through the forest, they came upon a man sitting serenely under a tree.

"Who is this man?" the Prince asked. "And why is he sitting here like this? I have never seen such clothes! Just an orange robe, and no shoes. All his hair is shaved off like a criminal, yet he looks to be--happy. Is he a working man? Or a priest? Surely he is not a soldier. Where does he live? How does he live?"

"So many questions! Channa laughed, "This man is a mendicant, My Prince. He lives with other monks in a place called a temple. Do you see that bowl in his hand? Each morning he and his fellows spread throughout the city, accepting gifts of prepared food placed in that bowl by the people. In exchange, they teach the citizens about how to be happy."

"Well, Channa, I like this lesson better than the others you have given me. Still, let's return to Kanthaka and go home. You have given me much to think about."

The Great Departure

When the Prince returned home, his father came out to greet him. "Good news, my boy!" he cried gleefully, slapping the young Prince's back. "Yashodhara has had a son!"

"A son?" murmured the Prince. "But this will forever bind me to the life of a householder." In their language, the word "binding" or "fetters" is Rahula, and that became the unfortunate boy's name. (We will learn his story another time.)

But the King's well-wishing would not be denied. First there was a grand celebratory feast, followed by musicians and dancing girls. This was to celebrate the birth, yes, but also Shuddhodana was hoping to lift the Prince out of the depression he had fallen into, and to convince him once again that life was good.

The plan, of course, backfired. Siddhartha was too distracted by his thoughts to enjoy the meal, which set him to thinking how useless was the luxury he had experienced all his life and had come to take for granted.

After dinner, during the entertainment, he was so exhausted that he fell asleep.

The Master of Revels, seeing this, told the musicians and the dancing girls to sit and relax. It wasn't long before they, too, fell asleep.

And what should happen but that the Prince should awake before them and behold! here he saw the most talented men and the most beautiful women in the kingdom, lying arms and legs akimbo most uncharmingly: some snoring, some scratching themselves, and others actually drooling!

It caused him to think: "No matter how young, no matter how beautiful, we can all manifest an unseemly side. This is a hint at the true nature of all things: we are born, we age, we ail, and we die."

He left the hall and, finding faithful Channa, asked him to saddle Kanthaka. While that was being done, he looked in on his sleeping wife and their newborn son.

"I hereby vow," he thought, "that once I find what I seek, I will return and do right by them."

(And so he did: Rahula later became a monk. King Shuddhodana also joined the sangha, and after the King's death the Prince's dear stepmother Prajapati became the first Buddhist nun, who ordained hundreds of others, including Yashodhara.)

"My Lord," Channa whispered, tugging at his sleeve. "Kanthaka is ready. Where are we going?"

"Down to the river, Channa. But not 'we'--I must go alone."

But Channa was adamant. "No! Your royal father would never forgiver me!"

"Very well, Channa," the Prince replied, "but you will leave me at last."

They went out the gate so quietly that later tradition says the gods supported Kanthaka's feet so the palace guards would not hear his hoofbeats. The Prince rode, with faithful Channa running behind, holding on to Kanthaka's tail.

After they reached and crossed the river (with a mighty leap by the stallion), Siddhartha looked back toward the city. "Look Channa," he said. "The city is wrapped in sleep. But I hereby vow that, when I have achieved my goal, I will return and help them become awake."

And as he spoke, he began removing the marks of his status--his headdress, his princely garments, his jewels and bangles--and, wrapping them in a bundle, he handed them to Channa. Then, using the sword he had removed, he cut off his royal topknot, then pulled simple clothes and a begging bowl from his saddlebags.

As he dressed, Channa sputtered, "Wha-- what are you doing, My Lord?"

The Prince said, "Now, Channa, take Kanthaka and return to the palace. Give my love to my father and mother, and to Yashodhara and Rahula, and tell them I will return when the task is accomplished."

"But--"

"No more delay, Channa. I must go."

"Can I not follow, My Prince? What is my purpose in the palace without you there? I have been with you virtually all your life!"

"No, Channa. This is something I must do alone. Imagine an ascetic attended by a servant!" And both men smiled.

With a lump in his throat, Channa reached for the horse's reins. But Kanthaka refused to move! At last Siddhartha came to him and said in his ear, "It's okay, boy. You may go now. Go with Channa. I will return." And with that he turned and began walking into the forest.

But Kanthaka sensed he would never see the beloved young man again. Tears rolled down the long face of the white stallion as he kept his eyes on the retreating Prince. And then the great beast's heart burst in his chest, and he died on the spot.

Notes on the Story

There's little to be said about this story, except that it most likely is a story.

Scholar Stephen Batchelor says that the earliest documents about the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, do not attach this story to him at all.

Instead it's associated with him through a kind of syllogism, that goes like this:

All Buddhas (this one and all the legendary ones preceding him) have the same life story.

This is said to have happened to a previous Buddha.

Therefore, it must have happened to the historical Buddha.

Pretty neat, huh? Maybe a little too neat?

Another thing we notice is the repetition of incidents with just a single, final variation. This is a standard story telling technique.

Each pig built his house of (straw, sticks, bricks) and along came a wolf.

Goldilocks found the bears' porridge to be (too hot, too cold, just right), and so on.

The Prince saw a/n (old, sick, dead, holy) man.

Note that the final case is always different, and makes the point:

The third little pig's house was able to resist the wolf.

Goldilocks's third try corrected the problems of the other two.

The holy man was finding a way out to avoid the causes of suffering seen in the first three outings.

So the "Four Sights" follow a classic storytelling structure.

--------

The story of "The Great Departure" seems to be closer to the truth, but still betrays the storyteller's art. Notice:

the timing of his son's birth

the (accidental) naming of the son as "fetters"

the lesson of the sleeping entertainers

the secretive slipping away from his family (something which some people who hear the story have criticized him for; but Jesus said, "If any man come to me, and does not hate his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yes, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple." So there's that.)

the gods muffling Kantaka's hoofbeats

Kanthaka's grief

I'm not saying it isn't so, but it all seems pretty convenient, doesn't it?

Nevertheless, as a story, it works. It's probably my favorite story about the Buddha's life, and I've told it repeatedly.

Different traditions vary on some of the details, large and small. To take a large example, some say he saw all the sights in one trip, some say (as I did) that he saw them on consecutive days, and others say it happened over a longer period. But smaller details differ, too: Some say Kanthaka died on the spot, for example, and others say he died back at the palace.

The amateur folklorist in me imagines finding kernels of fact in many of the details. Certainly the Buddha-to-be left home because he became aware of the suffering of life, however that may have become obvious to him; the "four sights" symbolize this. While he seems a little naïve to have come to this at age 29, I see it as more like one of history's most fortuitous mid-life crises. (A little early in life for that, perhaps, but things were different then.) The Chinese have a saying: shēng-lǎo-bìng-sǐ (生老病死). It means "birth, age, sickness, death." These are the four causes of suffering. (What is birth doing there? If we had never been born, we wouldn't experience the other three!)

There is also psychological truth in the idea that his crisis was triggered by the birth of his first (and, as far as we know, only) child. How many parents, and perhaps especially dads in traditional families (who bore the financial burden), have freaked out over the arrival of that first little bundle of joy?

The Prince leaves the palace without getting caught? Must have been the gods. His horse dies after he left? Must have been from a broken heart. I can easily imagine this kind of fantastic "spin" being put on some very real events.

Thus we make myths of the most mundane moments.

And whatever vestiges of religion still dwell in me also find the story meaningful in a pleasing way.

In short, as I said, the story works.

A few notes on names:

Siddhartha (in Sanskrit, Siddhattha in Pali) means "He Who Achieves His Goal," an eventuality he refers to twice in my telling.

Shuddhodana means "He Who Grows Pure Rice"; rice was the basis of the Shakya clan's power. As mentioned in Episode 124: "The Birth of the Buddha," Shuddhodana was not a king in the European sense, but more like a tribal or clan chieftain, perhaps even the head of an elected council.

Channa (in Pali; in Sanskrit, Chandaka) is perhaps from Chandra, meaning "the Moon." This may be significant, as the Great Departure is said in some traditions to have occurred on the night of the full moon in Ashadha, a month on the Hindu calendar that corresponds to parts of our June and July. Others celebrate it at Vesak, the full moon of May. (The Chinese don't celebrate it on a full moon at all, but it on the eighth day of the second month--this year March 7th--about a week before the full moon.)

Kanthaka can mean "thorn," perhaps, it has been suggested, a reference to the difficulty of leaving home. (Sounds pretty weak to me.) More significant is the tradition that says the horse was born on the same day as Siddhartha, and here we see him dying when the Prince "died" to his old life. Cool.

--------

Well, that's that! Until next time, may you and your loved ones and all sentient beings be well and happy.

Adios, Amigos!

GET MORE:

Find this and all past issues of the Newsletter online at Substack.

If you have any problems reading the Newsletter , please write to me at TheTempleGuy@GMail.com, and I'll help you in any way I can!

In the next episode: The tale of Hanshan and Shide, two Tang Dynasty poet-monks who stand as paradigms of friendship in China

What surprised me was that there were FOUR sights. I'm used to events happening in groups of three in stories.