Here is your monthly story available FREE to all subscribers. PAID subscribers get a new story every week!

"Have you heard it?" Sachiko asked.

"Yes, have you?" Yuki replied.

"Yeah. It was creepy!" Sachiko said, hunching her shoulders as she placed her hand over her mouth and laughed gently.

"Girls!" Sachiko's grandmother scolded. "Stop joking about it. This is serious!"

She turned back to Yuki's mother. "So you're saying no one has seen Natsu since the stone started crying out?"

"No," the other woman replied. "After her husband left for Kyoto, she continued climbing the hill to the temple every afternoon to pray for a safe birth for her baby. But the bonso says he hasn't seen her since she came on Butsumetsu. And it was that night that the stone was first heard crying."

"Butsumetsu!" the older woman replied. "She should have stayed home. That's the day the Buddha died! Nothing good can happen on that day of the week!"

"Well," said Yuki's mother, "with her due date so near, I guess she wanted to ensure that the birth would be a good one, and dared not risk skipping a visit."

"I suppose you're right," the other replied. "The bonso hopes she's had the baby already and is just lying in."

"That would be best," said her friend. "Still, it's odd that the stone started crying that very night. And after all, it was right on her route . . ."

--------

Meanwhile, as the day drew to a close, old Kotaro was preparing to close up his sweets shop when once again the ragged old monk entered--the one he had never seen until recently--and made the same request he had made over the last several days:

"Mizuame [sweet water], please."

"Yes, obousan," Kotaro said, addressing the monk formally. "I was expecting you, and had the syrup ready. Here it is." Handing over a small flask, he asked casually, "So, is it for an ill baby?"

But the monk left the coins on the counter and, without a word, turned and headed out into the gathering gloom.

This time, old Kotaro was ready. He dashed out, pulling the door behind him, and followed the sound of the monk's retreating wooden clogs. He seemed to be heading toward that weird stone that had started emitting crying sounds a few nights earlier.

Sure enough! There was the old rascal ahead, just by the rock, and bending over . . .

"Obousan!" Kotaro called out.

The startled monk straightened up and, without looking back, fled into the night.

Nosy old Kotaro went up to the spot where the monk had just been standing and, looking down, beheld--a baby! Was this the source of the crying so many had reported?

But no. As he picked up the nearly-newborn, wrapped in a bloody kimono, he distinctly heard the crying sound coming, not from the baby, but from the man-high round boulder next to which the infant lay.

A red stain ran down the rock, and at the top of it a triangle of steel was wedged into a gash.

"Come, child," he said. "Let's take you up to the temple and see what we are to do with you."

--------

Several nights earlier, on the afternoon of Butsumetsu, Natsu--about whom so many were worried--had indeed made her way up the hill to once again pray to Kannon, Bodhisattva of Compassion, for the safe delivery of her child.

"Oh, Kannon-sama," she prayed, using the most formal form of address, "You know how hard it will be for me to bear this child with my husband away. Through your compassion, please give me an easy delivery. But come what may, you know that nothing--nothing!--will prevent me from giving this child everything I have, even my very life!"

She prayed longer than usual, and suddenly realized that night was falling. So she rose up from her knees and fairly waddled to the door of the great hall, where she stepped down and trod the path out the gate and down the hill. When she reached the peculiar round boulder, she stopped for a spell and rested against it.

Just as she prepared to push on, a man sprang from the surrounding bushes and, ignoring all niceties, said, "Well, well, what have we here? A new mommy, I see? Well, Mommy, if you value your life and that of the child, give me all your money--now!" And with that he brandished a long sword.

"But sir," she said meekly, "I have no cash. What little I had I placed in the collection box in the temple hall as a prayer to Kannon."

"The temple?" he raged. "The TEMPLE?! Are they not rich enough already? Well, then, you and your brat shall pay!" And he swung his sword at her, ripping open her belly but missing the child.

However, he struck right through to the boulder with such fury that it broke the tip off his sword, lodging it in the rock.

Then, grabbing the woman's small bag as she fell, he ran off into the night.

As she slid down the rock, poor Natsu's blood left a smear. Her unfortunate baby was born from her wound and took his first breaths lying in her opened stomach.

Someone--presumably the old vagrant monk--had spirited away her body, leaving the baby swaddled in her bloody kimono. And that's how Kotaro the sweets seller found him.

--------

"Who's there?" called out Kyo'un, the priest at the temple. "Who's banging on our gate at this time of night?" Lighting a lantern, he made his way out of his quarters to the gate.

"Who is it?" he called again.

"It is I, bousan," answered a familiar voice. "Kotaro--and a small guest."

"A guest?" the priest said, working at the gate mechanism. "So late?"

"It is late for you, Kyo'un," the sweets seller replied with a chuckle. "But barely past dinnertime for us common folk."

"Well, then," the priest said, swinging wide the gate. "Welcome. And who is this?" he asked spotting the child.

So Kotaro told him of his experience--about the tattered monk who bought the mizuame every night since Natsu had disappeared, and how he had found that same monk administering the sweet water to the baby.

"A monk, you say?" mused Kyo'un. "I suspect there's more to this than meets the eye."

"Do you think it was Kannon-sama himself?" the old shopkeeper asked.

"Could be," said the priest. "If prayers mean anything, Natsu's were enough to guarantee this child the Bodhisattva's protection."

"But what shall we do with him?" the shopkeeper asked.

So the two men put their heads together and devised a plan: the boy would grow up in the temple, and the sweets seller would provide mizuame and whatever else he could for his upbringing. "I am not wealthy," he told his old friend, "but it would be a pleasure to help. Besides, with no children of my own, I might want someone to take over the shop someday!"

It was settled. Otohachi (for that's what they named him) was to live with Kyo'un, but Kotaro was to "co-parent," as we might say today.

Kyo'un was a kindly foster-father and a proper priest. He set up a memorial to Natsu in the temple and, when Otohachi was old enough, taught him to offer incense for the soul of his mother.

Nevertheless, the stone could still be heard to cry at night.

On long winter nights, Kyo'un told the lad the story of his birth, and in due time showed him the steel piece that Kotaro had prised out of the boulder. Otohachi took to carrying it in a pocket inside his kimono as a kind of good luck piece.

Through all of this, the old priest inadvertently instilled in the boy feelings of vengeance.

"But how can I ever succeed at such an impossible task?" Otohachi wondered.

--------

When Otohachi became of age, Kotaro called to him in the temple garden one day.

"Come sit, my boy, while I catch my breath from the climb up that hill."

"I'm sorry, Otousan," the boy said, calling him "Father" just as he did the priest.

"Actually, Otohachi," the old man went on, "I have come to talk to you about your future. The climb up that hill seems to get longer every day, and I'm thinking it may be time for me to retire."

"Oh, that's wonderful, Otousan! Then you can spend more time with us!"

"Perhaps, boy, perhaps. But you know, I have always hoped you might take over the shop when the time came."

"Oh!" the lad cried, his face falling. "But Papa," he said, addressing Kotaro as he did when he was a toddler. "I can't! I mean . . ." And here his face was so wracked with pain that the kindly old man was moved to comfort him.

"There, there, boy," he said. "That's all right, I'm sure I can find another to take over for me. Maybe my sister's grandson. But what is it that prevents you?"

"Well, Otousan," the boy said, recovering his composure. "It's just that . . . well, when I pray in front of the temple's Kannon--the same one I'm told my mother prayed to--I feel moved somehow to . . . another profession."

"And what is that?" asked the sweets seller.

"Well, I don't know if it's possible, but I really wish to be apprenticed to a sword maker."

"A sword maker!" the old man exclaimed. "Why ever--?"

"I have this sword tip," the boy explained, pulling out the "souvenir" Kotaro had dislodged from the boulder so long ago. "And when I hear the stone crying at night, it feels heavy in my pocket, and I just think--"

"I understand," Kotaro said. "I won't say I'm not disappointed, but you know your other father and I would do anything to see you happy. Tell you what: One of my neighbors, Yoshimatsu, is a sword maker--"

"Oh, yes! I've been in his shop!"

"I know, and he was impressed by your seriousness," the old man went on. "Let me speak to him and see if we can arrange for you to go to work there."

--------

And so it was decided. Otohachi went to work in Yoshimatsu's shop, and began to learn the trade. First, though, he was relegated to the usual tasks for an apprentice: sweeping up, bringing in coal for the forge, and minding the shop when Yoshimatsu was out on business.

One day, after he had progressed to the level of journeyman, he was sitting alone in the shop when a rough old man came in. His beard was unkempt and his kimono filthy. Nevertheless, Otohachi rose and asked courteously, "Yes? How can I be of service?"

"I have this old blade," the ruffian said, pulling a long sword out from under his robe, "and you need to repair it."

"Lay it on the counter there," the young man said. When he did, the lad stood for a moment, agape. At last he stammered out, "What happened to the tip of your sword?"

"Oh, that! Heh-heh," the man laughed, trying to be casual. "I was once, um, waylaid on yonder pass, and set upon by bandits. In the ensuing fight, I, uh, struck a boulder up there and the tip sort of just broke off."

Picking up the sword, Otohachi slowly reached into his kimono and pulled out the sword tip. It fit perfectly!

"Stand and be counted," he said to the rogue, "for I am Otohachi, son of the very woman whose life you took for nothing! I am the child whose life was spared, no thanks to you, and now it is time to avenge my mother's death!"

And with that he took off the scoundrel's head.

And all the people marveled that the "Night-Crying Stone" was evermore silent.

Notes on the Story

I have improvised much of this story, the bare bones of which can be found in several versions. I have picked and chosen between a number of them. For an account of the temple that claims to have one of the two stones associated with this story, see Episode 105: Japan's Night Weeping Stone.

The name "Otohachi" is found in the original texts. Its characters, 乙八, are hard to decipher. The first has multiple meanings, from "second" (including something like a "B" grade) to "stylish" to (to me the most likely) "strange, quaint, or queer." The second character is straightforwardly "eight." But I cannot reconcile these to the story, except perhaps for the "strange" one. But "Strange Eight"? I got nuthin'.

The other men's names in the story are taken from a list of common names in the Edo Period (1600-1868), except for the name of the priest. "Kyo'un" is my attempt at rendering "Xuyun," the name of one of my favorite Chinese monks, into Japanese.

All of the women's names are made up, as are the women themselves, and many other elements of the story: the sword tip in Otohachi's possession, the dialogue (of course), Kotaro's desire to leave his shop to Otohachi, and much more.

I have also chosen to call the religious man at the temple a "priest," to distinguish him from the wandering monk (suggested to be Kannon). In common usage, Buddhist establishments are called "temples," and their residents "monks." Shinto, the native religion, has "shrines" and "priests." However, this becomes less clear-cut when we realize that many temple managers are family men, with a wife and children, making them different from the image of the celibate monk.

There are also some major plot holes in my sources. Nothing is ever said of the disposition of the murder victim's body. Nor are we told whether the baby cried, though some versions suggest--as Kotaro speculates--that that is what the neighbors heard. And again, we're never told when the stone stopped crying--but it must have, because the one I saw was silent!

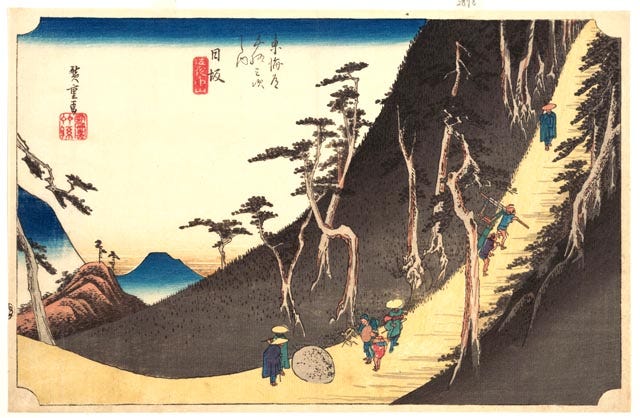

But the mizuame is an authentic part of the story, and is still sold in the area of Kyuenji, the temple I visited while walking down the Old Tokaido in 2001 that has one possible specimen of the "Night Weeping Stone."

The stone at Nissaka, the story of which is described here, is only one of a half-dozen or more yonaki-ishi or "Night-Crying Stones" in Japan. Another is in a park in the Tokyo area, on the site of an ancient battlefield. As the story goes, the daughter of one of the samurai who fell came to hold a ceremony for the fallen and, overwhelmed by the sight of the dead, fainted away and died. A nearby stone cried out thereafter, until another samurai came and hosted a ceremony to put to rest the soul of the young girl.

--------

And that is all that. Until next time, may you and your loved ones and all sentient beings be well and happy.

Adios, Amigos!

GET MORE:

Find this and all past issues of the Newsletter online at Substack.

If you have any problems reading the Newsletter , please write to me at TheTempleGuy@GMail.com, and I'll help you in any way I can!

In the next episode: How did Bodhidharma come from the West?