Here are two stories about extraordinary gifts given by the man we know as Ashoka the Great, also called Dharmashoka, or "Ashoka the Righteous." One was given in a previous birth, and the other on his deathbed.

--------

A Gift of Dirt

"Vijaya, come quickly!" the boy called out. "See this house I built? It is much like the one my father built for my family!"

Vijaya ran up and, certainly, this was the mansion of his friend Jaya's father, faithfully reproduced in the mud they had been playing with.

"Yes, Jaya," he said. "That is large and grand, the very image of your house. Not small and shabby like mine."

"Never mind, Vijaya," Jaya answered, throwing an arm around his shoulder. "The size of our houses doesn't matter. All that matters is that we are good friends, and shall be forever!"

"But still--" Vijaya began to reply, when his words were interrupted by a tremendous SHOUT, one such as the boys had never heard in their young lives.

"What in Jambudvipa was that?" cried Vijaya, using the name of the known world.

And taking his hand, Jaya replied, "Let's go and see!"

As the boys made their way through the streets, they saw many inexplicable sights.

In one street, a man was moving toward them, looking this way and that but mostly gazing at the sky as though taking it all in. "Jaya," Vijaya whispered, "was that not Vikram, the blind man? It appears as though he can see!"

"Yes, that was Vikram," Jaya said, and as he spoke, Kumar, the lame man, ran past them, practically leaping with joy.

"And there's Kumar!" he continued, "but how--" and here he ran headlong into a woman. "Excuse me, mother," he said, and when she replied, "That's all right," he realized it was Mira, the woman they had always known as deaf and mute.

"Did you hear that?" he said to Vijaya. "Mira just--"

"I know! She heard and answered you!" Vijaya marveled.

And perking up their own ears, they realized that they--like Mira--were hearing the most wonderful sounds all around them: the trumpeting of elephants, the warbling of birds, the beat of drums that no one was playing, and--they were told later by their aunties--even the tinkling of jewels in women's jewelry boxes.

They were also to learn that slaves bound in fetters had been miraculously freed; that men who had been mortal enemies for years now felt nothing but love for each other; that calves who had been sold had broken free and returned to their mothers; and that--some swore--rough places were made smooth, and crooked places straight.

--------

Whence these marvels?

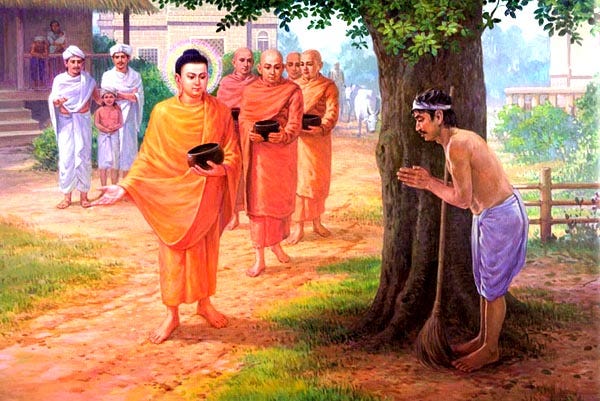

Unbeknownst to the two boys, that morning, the Blessed One--the Buddha, who was still in the world at that time--had arisen, donned his robes, taken up his bowl, and, surrounded by his devotees, made his way into Rajagriha to beg for alms.

Later chroniclers asserted that "with his body like a mountain of gold, and his gentle face like a full moon, he went forth at a stately pace, like a lord of elephants."

Then, arriving at the city gate, he set his foot on the stone threshold, and it was this that had engendered the prodigies witnessed by the town. For millions of ages past, whenever a Buddha entered a city and placed his foot on the threshold stone, such wonders would occur.

The exuberant shout that the boys had heard was the elation of the men and women who had been converted by these miracles.

--------

As Jaya and Vijaya tumbled forward they came to a wall of people: clearly something was stirring along the town's main street and, so as not to miss it, the friends ducked under legs and arms and climbed over carts blocking the way--as boys will--until at last they were in the very front of the crowd lining the street.

And here it came! Not the procession of a king with his elephants, nor the delights of a party of entertainers, but simply the progress of a group of--monks?

What was so exciting about that?

But then Jaya caught sight of a figure in the midst of the hubbub.

"Vijaya! Look!" he said, tugging at his friend's tunic. "Could that be the Great Teacher about whom we have heard so much?"

As the boys looked, they saw the Buddha with his pleasing appearance passing by.

Without hesitation, Jaya--thinking that it was ground meal he had in his hand--threw something into the Buddha's begging bowl. But it was dirt! Vijaya at that moment placed his hands together and bowed.

Once he had made this offering, Jaya conceived a great resolution: "Beginning with the merit derived from this act, may I become such a king that all Jambudvipa falls under my umbrella, and I will cause the whole Earth to pay homage to the Blessed One."

The Buddha, seeing past the gift to its intention, saw that it was good, and saw that the seed of good karma that had been planted would someday bear fruit.

And so the boy Jaya was reborn a few centuries later, to become Ashoka the Great. And his friend Vijaya was reborn as Radhagupta, his prime minister, whom we shall meet again in a moment.

Ashoka's Last Gift

The King was dying.

Confined to his quarters, he called to him his Prime Minister and friend, Radhagupta. "Radha," he asked feebly, "Do you remember the vow I made to the Kukkutarama monastery?"

"Of course, Your Majesty," Radhagupta replied gently. "You promised them that you would give them one hundred kotis pieces of gold." [One koti is equal to 10 million.]

The troubled King then asked, "And where does my account stand?"

Radhagupta answered from memory, "At 96 kotis of gold pieces, My Lord."

"Tally it up for me, Radha," the King ordered.

"Well, Lord," Radhagupta began, pulling a palm-leaf manuscript from his robes, "you built eighty-four thousand stupas to enshrine the Buddha's relics, and endowed each with one koti."

The King interjected, "So that was eighty-four kotis."

"Absolutely correct, My Lord. You then donated one koti to each of the four places specially marked out by the Blessed One as worthy of pilgrimage after His passing: His birthplace at Lumbini; Bodh Gaya, where He was enlightened; the Deer Park at Sarnath, where He preached His first sermon; and the place of His death and attainment of final Nirvana at Kushinagara. Oh, and not to forget, the four kotis you graciously spent on a feast for three hundred thousand monks."

"That's only 92 kotis, Radha. Is my old friend perhaps losing his skill with numbers?" the King teased affectionately.

"Ever perceptive, Your Grace, ever perceptive. I was just getting to that," Radhagupta said, glancing at his manuscript. "Let us not forget, you donated… let me see… the whole earth (saving for the Royal Treasury), your harem, all the state officials (including myself), your son and heir, and even your royal self."

"Ah, yes!" laughed the King softly. "I remember now; I had to redeem them for--four kotis, was it?"

"Exactly, My Lord, and that brings the total to precisely 96 kotis of gold pieces."

"And so, Radha, you are correct--but I have come short of my goal."

After falling silent for a moment, the King continued.

"I remember the day," he said as though reciting a familiar story, "that I called to me Yashas, the abbot of the Kukkutarama monastery--"

"Which you graciously founded--"

"Yes," he affirmed, waving the flattery away with his hand. "I asked him who had been the Blessed Buddha's chief donor when he was in the world, and he cited the wealthy merchant Anathapindika, who donated the great monastery at Jetavana Grove. When I asked him the total value of contributions to the Blessed One made by this householder, he replied--"

"Exactly 100 kotis of gold pieces, Your Grace, and you declared to all present that you would match that."

"Yes, Radha," the King replied. "It was not seemly for the generosity of a trading man to outshine that of a King. But now my days are short, and I have fallen short."

Quietly his old friend chided him. "Is the visage which once made your enemies tremble, and which has been kissed by hundreds of lotus-lipped beauties, now covered with tears?"

"Mistake me not," the King rallied. "I do not lament losing my wealth, my royal privilege, or even this body. But I do lament that I have failed the Aryas--the Noble Ones--who have given so much to me and my kingdom. Moreover, I shall hear their teachings and behold their examples no more. That is what causes me to shed tears."

Nevertheless, with the time left to him, the King set out to finish what he had started. One way or another he would give four more kotis of gold pieces to the Kukkutarama.

---------

But it was not going to be so easy. Ashoka's grandson, Sampadin, was now the heir apparent. (His father, Ashoka's son Kunala, had become a monk and then was blinded through the treachery of his stepmother.)

So when Ashoka began distributing more wealth to the Kukkutarama, Sampadin's ministers advised him to put a stop to it, as the royal power was dependent on the Royal Treasury.

In a quiet coup, then, the king's control of the Treasury was withdrawn.

However, he still had power over the gold plates, goblets, and cutlery from which he dined; after each meal, he had these sent to the monastery. When that ploy became known, the courtiers served his meals on a silver service; the King sent these, too. And it happened again, with copper.

Until at last, Ashoka the Great, Ruler of All Jambudvipa, was reduced to dining on clay plates and drinking from clay goblets.

The day came when the King could be found sitting and reflecting that all that was left to him was half of a myrobalan, a fruit valued for its medicinal properties.

In a fit of temper, he called together his court and asked, "Who, ye vipers, is Lord over All the Earth?"

Bowing before him, hands folded and knees trembling, the courtiers spoke as one voice, "You, Your Majesty, are Lord over All the Earth!"

But Ashoka would not be assuaged. "Do you think," he roared with a strength he did not feel, "that your lies will be effective? Do you think I do not know that, although I am still alive, my power has been usurped by my grandson and his minions? Do you think I am unaware that, far from being Lord over All the Earth, I am nothing but the Lord of Half a Piece of Fruit?

"I once stood to mortals as Indra stands to the gods! But I am instead impoverished.

"It is as the Blessed One taught us: 'Fortune leads to misfortune.' No one obeys me any longer. No one lets my orders stand: they are constantly reversed. The world was once under my sway, the hosts of the enemy fell at my command, the poor and dispossessed were comforted by this hand, now holding half a fruit before you. Even a mighty tree can be felled when its roots are cut!"

He then dismissed them all, save one of his faithful serving men.

"Ravindra," he said, "do your king this one last service: take this half a myrobalan to the Kukkutarama, and there offer it to Abbot Yashas and the Sangha. Make the proper obeisances and explain that in this humble piece of fruit lies all the power remaining to the once-great King Ashoka the Righteous. Request that they prepare this final offering in such a way that the whole community is able to benefit from it."

Ravindra sadly set out to fulfill his commission, and when he stood before Yashas the abbot, and the elder monks, he offered full prostrations to them before conveying the King's message. "My Royal Sovereign once warmed all of Jambudvipa like the noonday sun," he said, "but alas! he has now lost power like the setting sun at dusk. He humbly offers to you this fruit, which is all that he has, and requests that it be distributed throughout the monastery."

After murmuring among themselves, the elders called together the entire Sangha.

"Monks," Yashas said, "it is unseemly for sworn disciples, many of us arhats, to let go our equanimity and betray emotion. But in the event of the loss of our dear brother and patron, it is permitted that we grieve, not for ourselves, but for he who once was the Lord of Men. Who could not be moved by such a pass? Once the Lord of Jambudvipa, he is now Lord of Half a Myrobalan. His servants have stolen his sovereignty while he yet lives. This gift, all that he has left, serves as a lesson to all, commoner and royal alike."

He then instructed the kitchen to mash up the fruit and place it in a soup to be consumed by the entire Sangha.

When Ravindra returned from the Kukkutarama, Ashoka called Radhagupta and asked, "And now, Prime Minister, tell me: who is now Lord over All the Earth?"

Prostrating at Ashoka's feet, Radhagupta replied, "It is now as it ever was, Your Grace. Your Majesty is truly Lord over All the Earth."

Wincing with pain, the great King struggled out of his chair and, after facing the four directions with agonizing movements, he bowed profoundly in the direction of the Kukkutarama and pronounced, "Then, as Lord over All the Earth, I leave all the Earth--save for the Royal Treasury--to the Sangha of the Blessed One's followers. Wrapped in its ocean like a blue scarf, bejeweled by its many mines, capped by its snowy summits, I leave it all to the Noble Ones. May its fruits bring them benefit.

"I make this offering as a token of devotion, seeking no reward, save this: the power over my own mind."

He then had the gift memorialized in a document sealed with the bite of his own teeth, and passed away.

--------

Sampadin and his ministers made a great show of respect to the King's body before they cremated it, and quickly started making preparations to crown the new king.

"Hold, My Lords!" commanded Radhagupta. "Let us not forget the last act of the new king's Sovereign Grandfather: he has gifted the entire Earth to his beloved Sangha. If you are to become Lord over All the Earth, it first must be redeemed."

"What?!" cried out the King-to-be and his ministers in alarm. "This is an outrage!"

The outgoing Prime Minister produced the document sealed with the King's teeth, and there was no denying its validity.

"Very well, if that was my Grandfather's wish," said Sampadin. "And what, may I ask, will it cost us?"

"It had been the wish of the great Ashoka," the wily Prime Minister offered as his last official act, "to match the generosity of Anathapindika, donor of the Blessed One's monastery at Jetavana Grove. To do so, he would have had to donate 100 kotis of gold pieces, but alas! through your maneuvering he was stymied after giving just 96 kotis.

"It has been given to me to know," he continued, "that the monks will settle for a ransom of only... four kotis."

So the ransom was paid, the Earth was placed in the hands of the now-consecrated King Sampadin, and the vow of Dharmashoka, Ashoka the Righteous, Ruler of Jambudvipa, Lord over All the Earth, was at last fulfilled--more than making up for his one-time Gift of Dirt.

Notes to the Story

Not much is certain about the life and activities of the historical figure we call Ashoka the Great, who may have been born just a couple of decades after the death of another "Great," Alexander, who had died in 323 BCE.

We know that Ashoka was the third king of the great Mauryan Dynasty, founded by his grandfather Chandragupta around the time of Alexander's untimely and unexpected death in Babylon (modern Iraq) at the age of 32.

Chandragupta took advantage of the unrest that arose after the Greek conqueror's demise. The empire he founded was eventually to spread across northern India all the way from Afghanistan to Bangladesh, and included Pakistan and Nepal.

By all accounts, Ashoka was a brutal conqueror. What we know of him comes from rock inscriptions he himself commissioned, as well as Buddhist texts (some of them recorded long after his lifetime, containing varying amounts of legendary material). Archaeological evidence and even coins add to the information--and sometimes the confusion.

A very brief outline of the facts as (usually) agreed upon is this: he ascended to the throne after (allegedly) killing the crown prince (his half-brother) and 98 other half-brothers who might have challenged him.

Having established his reputation as "Ashoka the Fierce" (Chandashoka), he set out to expand the empire. We are told that, after one particularly bloody battle in the Kalinga region in the eighth year of his reign, he was suddenly moved by the slaughter he had wrought and became dedicated to the Buddha's peaceful teachings (the Dharma), becoming known as "Ashoka the Righteous" (Dharmashoka).

These accounts were written by Buddhist monks, and are likely to have exaggerated both the level of his ferocity (he was said to have personally beheaded 500 ministers, burned to death 500 concubines, built a jail and torture chamber called Ashoka's Hell, etc.) as well as the suddenness of his "miraculous" conversion. As we know, such things rarely are so clear cut.

I have mentioned the "Rock Edicts"; Ashoka is believed to have placed more than thirty such inscriptions, many of them mentioning the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Others discuss ethics and politics without specific mention of Buddhism; these are thought to teach the proper order of society (Dharma in its larger sense, of "duty").

Some of the "Ashoka pillars," like the one marking the birthplace of the historical Buddha, confirmed the location of important sites, to the benefit of everyone from ancient Chinese pilgrims to scholars during the British occupation

Ashoka is also credited with patronizing the Third Buddhist Council to settle disputes in the Sangha, and with collecting and redistributing relics of the Buddha, building (according to legend) 84,000 stupas (other sources say "monasteries") to hold them.

At any rate, one of the great legends about his life is contained in a text called the Ashokavadana ("Narrative of Ashoka"). It gives a fascinating version of his life story, starting with a previous birth of a monk, Upagupta, who became his teacher; and ending with the career of one of his descendants, Pushyamitra, who attempted to wipe out all the good he had done (underscoring the Buddhist principle of *impermanence).

Along the way, we learn of

Ashoka's previous life as the boy Jaya;

his boyhood under his father, King Bindusara (son of Chandragupta);

his ascent to the throne;

his conversion to, and promotion of, Buddhism;

the conversion and death of his brother, Vitashoka;

the story of his son Kunala, who, in a bit of palace intrigue, was blinded while away from home and, after attaining enlightenment, became a wandering beggar monk-musician; and

his final illness, when he tried to give away the resources of the royal treasury and became "Lord of Half a Piece of Fruit."

Some of these stories are worth looking at in future episodes; in the meantime, you might check out my main source, the translation of the Ashokavadana by scholar John S. Strong, published as The Legend of King Aśoka.

--------

And that's that! Until next time, may you and your loved ones and all sentient beings be well and happy.

Adios, Amigos!

GET MORE:

Find this and all past issues of the Newsletter online at Substack.

If you have any problems reading the Newsletter , please write to me at TheTempleGuy@GMail.com, and I'll help you in any way I can!

In the next episode: Twelve Tales of Guanyin, Part I