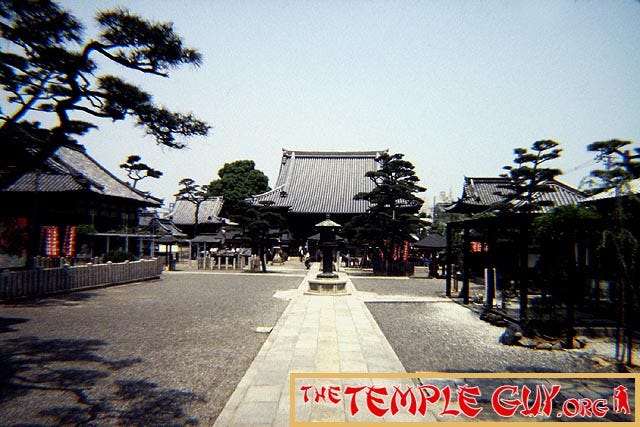

Fujii-dera, a temple named for a family with Korean roots (and remember, Buddhism came to Japan via Korea)--which family in turn was named for the arrowroot or kudzu vine--is found in a rather unlikely place: it's at the end of a shopping street in a suburb of Osaka, Japan's third-largest city, after Tokyo and Yokohama. Learn more about it in this episode of

TEMPLE TALES!

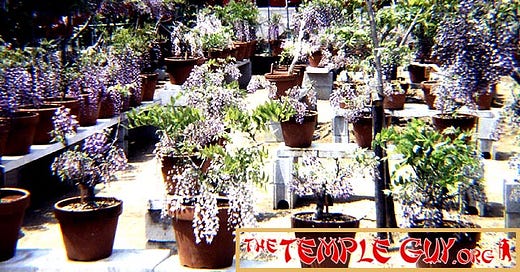

There's not much to the temple these days…

The Kokubun-ji System

Fujii-dera was built by imperial order in 725, and was originally quite massive. Pleasant as it is, it's now just a shadow of its former self. Its size was due to its role as a kokubun-ji, part of a system of temples commissioned to pray for the nation and the imperial house and, not coincidentally, to aid in the unification of Japan. There were two such temples in every province, one for monks, and another for nuns (called properly kokubunni-ji).

I have been to numerous kokubun-ji temples--some in ruins--including all four of those for the four provinces of Shikoku (see Episode 039) as well as Todai-ji, home of the Great Buddha of Nara, which was the headquarters for the entire system. Incidentally, koku means "country," and bun means "division"; a kokubun was a division of the country.