Note: A map that includes Sinagua ruins and other ancient native and mission sites in Arizona can be seen on my page, the Temple Guy.

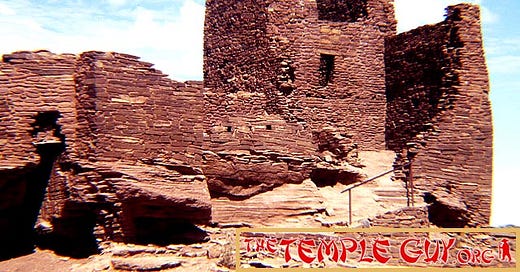

Had I known at 18 what I knew at 33, I might have been an archaeologist, and a major focus of that interest is likely to have been the relics of the Sinagua people around Flagstaff, Arizona, some of whose ruins we'll visit in this episode of

TEMPLE TALES!