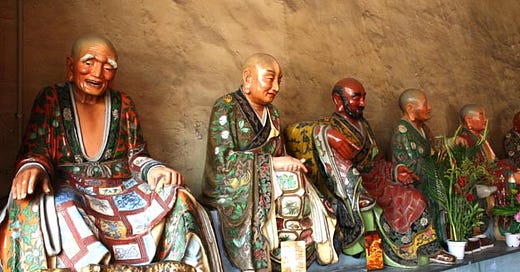

As we enter a temple's main hall, we may see on either side of us 18 odd-looking characters, nine to a side. With a little imagination, we can picture them listening to the Buddha teaching from the main altar.

And indeed, these 18 belong to a much larger group of shravakas or "hearers," a term that describes anyone who has taken refuge in the Triple Gem: the Buddha, the Dharma (his teachings), and the Sangha (the community of his followers). Let's start meeting them one by one in this episode of

TEMPLE TALES!