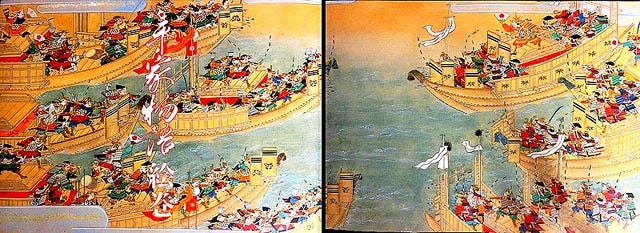

From time to time I'll be sharing well-known stories from Japanese and Chinese culture. These Episodes are not based on any of my journeys--thus, no original pictures!--but they should help round out our understanding a little. (I'll illustrate them from public domain sources as much as possible.) So please enjoy this episode of--

TEMPLE TALES!