In November of 1998, I made my first visit to the ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto--and was smitten for life. I had bought a little pocket-sized guidebook entitled Illustrated Must-See in Kyoto, so I rented a bicycle from my guest-house, and--taking that title to heart--saw almost all of the sites in it (nearly 30, by my count) in that first four-day trip!

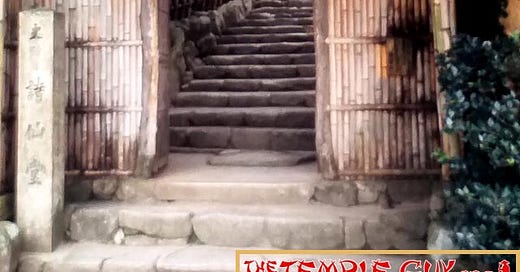

One of these "Must-Sees" was a precious little jewel to which, alas, I have not returned since. It lives in my memory as a near-paradise, as its maker intended it. So come with me and take a quick peek inside Shisen-do, the "Hall of the Poet-Immortals," and meet its now immortal creator, in this episode of--

TEMPLE TALES!