Ep. 047: Kukai: A Japanese Monk in China

See four sites of a great master's Tang Dynasty study sojourn

One of the peak experiences of my life was completing the 88 Temple Pilgrimage on Japan's Shikoku Island, dedicated to the life and teachings of Kukai, a Buddhist monk also known as Kobo Daishi. But even after 31 days on the pilgrim's path, I wasn't done with the Daishi yet! Let's take a look at significant sites from his study tour of China in this episode of

TEMPLE TALES!

[Note: Throughout this episode, I'll be referring to Yoshito S. Hakeda's magisterial Kukai: Major Works, a must-have for any serious student of Shingon and the Daishi.]

In late 2001 I completed the month-long circuit around Shikoku, Japan's fourth-largest island and the site of its most famous pilgrimage. (You can read highlights of my journey in Episode 039). The route was inspired--if not actually founded--by a native of the island whose monkly name was Kukai (774-835), "Sky [or space] Sea," but whom the Japanese emperor granted the posthumous title Kobo Daishi, or "Great Master Who Spreads Widely the Buddha's Teaching." His body rests today on Mount Koya, which we visited in Episode 032.

The Chinese Connection

Despite his roots in Japan, though, this episode is set, not in that country which was my home for nearly five years, but in another where I lived for over eleven: China, "The Middle Kingdom."

Buddhism, as we know, is native to India. It spread to China by various means--largely via the so-called "Silk Road" (of which there were actually many, including a maritime route), taking root as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), with claims that the first official temple, named "White Horse" (Baima) for the missionary monks' form of transportation, was established in the then-capital Luoyang in 68 CE. (We'll visit there sometime.)

In any case, China is the well-spring of Buddhist teaching in East Asia. Although Buddhism arrived in Japan via the Korean kingdom of Baekje, direct ties were soon established with Chinese institutions (whence the Koreans had also received the teachings). Despite the rigors of travel in those days, the record is replete with Chinese masters going to teach in Japan, and vice versa.

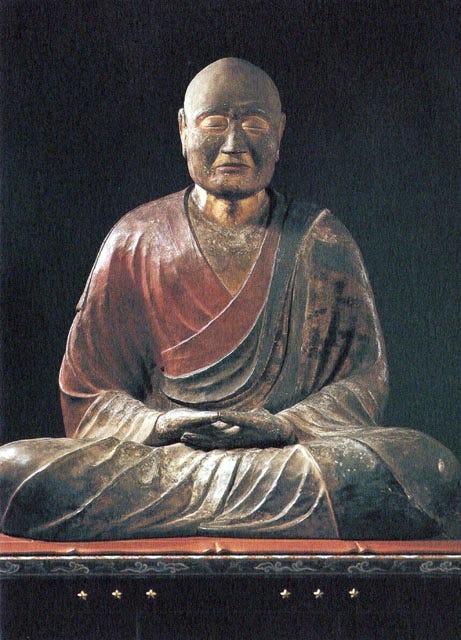

A copy of this statue of Jianzhen (Ganjin) at Toshodai-ji in Nara (which he founded) was presented to Daming Temple in Yangzhou as a token of Sino-Japanese Buddhist cooperation. (from a postcard purchased at Japan's National Gallery, where I saw the statue close-up)

One example of the former is Jianzhen (Japanese Ganjin, 688-763), who in his late 50s responded to an invitation to teach in Japan. That attempt failed, as did three more (whether due to unfavorable weather or government prohibition). On his fifth attempt, a storm blew him all the way around the coast to Hainan Island, not far from Vietnam. His return home took three years, during which he was blinded by an infection.

At last, blind, and 64 or 65 years old, his sixth try was successful, and he taught in Nara until his death 10 years later. I had the privilege of living and teaching for a year in his home temple in Yangzhou, Daming Temple, where Japanese devotees contributed a copy of a famous statue of Jianzhen, and built a lovely Tang style hall and courtyard to house it.

Like Kukai after him, Jianzhen had studied in the Chinese capital of Chang'an, modern Xi'an. During the "Glorious Tang," Chang'an was quite the cosmopolitan center. Professor Hakeda says that shortly before Kukai visited in the early ninth century, the city had "sixty-four Buddhist temples for monks and twenty-seven for nuns; ten Taoist temples for men and six for women; and three foreign temples. Of the three foreign temples it is certain that one was Nestorian Christian and one was Zoroastrian or Manichaean. Moreover, the number of Moslems in Chang'an was increasing."

But Kukai's journey from Japan to Chang'an, though not quite as fraught as Jianzhen's to Japan, was still no walk in the park.

The Landing Spot

In the summer of 804, four ships left Japan. Kukai was on Number One. (There is a great deal of discussion as to how this came to be. Hitherto he had been something of an obscure mountain ascetic, so how did he find a slot on an official government expedition? Anyway...) The first ship, Kukai's, was blown off course and landed in Fujian a month later. The second, bearing Saicho--Kukai's contemporary and sometime rival, founder of the Tendai (Chinese Tiantai) sect in Japan--landed in Ningbo after about two months. The third ship returned to Japan, and the fourth was lost--with just one survivor.

The Konghai (Kukai) Memorial Hall looks Japanese-y to me, but I was assured it was "Chinese Tang style."

The place where Kukai and his companions landed was not accustomed to receiving foreign visitors. The ship was impounded, and the passengers and crew housed in a miserable swamp for two months. But Kukai wrote a letter to the governor in the name of the envoy he was traveling with, and--apparently impressed--the governor moved them to better housing, where they awaited word of their fate from the capital. Approximately four months after leaving Japan, they set out overland to Chang'an, reaching there a month and a half later.

But let's go back to that swampland.

In July of 2006--1202 years after Kukai left Japan, and in the same time of year--I had the privilege of teaching 100 or so kids in a temple in Fujian. (You can read about it in Episode 006, "At a Mountain Hermitage.") On the day I was to fly home, Venerable Dun Chao, the monk who was driving me to the airport--and who knew of my interest in Kukai, whom the Chinese call "Konghai"--suggested we visit a very special place--"very near" he said. You see, the temple where I had volunteered was in the city of Ningde, Fujian, which happens to be the place where Kukai landed!

Kukai on the altar of the Memorial Hall near his landing place

So we drove about 60 miles in the opposite direction from the airport to an area of rice fields not far from the sea--perhaps once a swamp--in Xiapu County. There we found the Konghai Dashi Memorial Hall. Japanese devotees had paid for construction of the Hall and its furnishings. When I commented to Ven. Dun Chao (through our interpreter) that it looked "Japanese," he replied curtly that it was "Chinese Tang style." That's no coincidence, as the style of the Tang was adopted by the Japanese in that era.

Kukai seated on the poop deck of a ship model

It's a single hall, with modest but attractive grounds. On the main altar is a standing figure of Kukai dressed as a monk with beads--not, as he's sometimes portrayed, as a pilgrim with a backpack and a staff. There's also a scroll depicting him seated on a chair in meditation--a very familiar sight--and a small ship model in which his out-sized figure is seated on the poop deck.

The Living Quarters: Ximing Temple

Now let's move on to Chang'an, called Xi'an today. I have visited the city three times: once on that crazy one-night-one-city 2007 business trip, described in Episode 035; again with my wife in 2009; and finally (for now) in 2010. On the first trip I managed to get to one Kukai site, Qinglong Temple; on the second I stayed close to the city walls and saw one more, Daxingshan Temple; and on the third I mostly ventured out into the countryside where I saw a third, Ximing Temple, though I did squeeze in a return visit to Qinglong, which I had seen back in 2007.

But here, I'll place my third temple first, as Ximing is the one in which Kukai was quartered; then we'll look at Daxingshan; and at last to Qinglong, where Kukai received transmission from his Master--which is why I had zeroed in on that one in 2007!

--------

On the eleventh day of the third month of 805, the Japanese envoy with whom Kukai had been staying returned to Japan, and Kukai moved into Ximing Temple. Here he stayed through most of his sojourn, studying and using it as a base for visiting other temples and their Masters.

The superb Main Hall at the restoration of Ximing Temple

From what I can gather, the Ximing Temple that Kukai had known was once very near the city's south gate--and is long gone, though parts of it have been excavated. I thought it might have succumbed to the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of 845, when Emperor Wuzong attempted to cleanse China of foreign influence, including those Zoroastrians, Nestorians, and Manichaeans mentioned above, and--perhaps surprisingly--Buddhists. Buddhism was, after all, an import from India. (Islam, incidentally, was spared in the Persecution, as it had not yet really developed any power. The emperor seems to have had economic reasons for the Persecution as well: bells and other bronze ornaments were melted down for coinage.) But Professor Hakeda says unequivocally that Ximing is "one of four temples in the capital that escaped destruction" in the Persecution. In any case, it's gone now.

But I was pleased and surprised when my research turned up a Ximing Temple after all--one located around 30 miles out in the boondocks from its former location.

Three shiny new Buddhas inside the Main Hall of a very "old" temple

To be honest, there's not much there. Its exquisite little compound (approximately 165 by 280 feet as measured on Google Maps) is now occupied by a group of nuns. The only large-ish hall is the Main Hall (which had a ceremony in progress when I visited), with a tiny Heavenly Kings Hall in front of it and a few other buildings arranged around it. One of these contains "patriarchs"--not surprising, as so many great monks once lived in the original, including Xuanzang (602-664), who had traveled to India and brought back scriptures which he translated "here"; another translator, Yijing (635-713), who also traveled to India as well as Srivijaya in modern Indonesia; Xuanzang's Korean disciple Woncheuk who took the temple's name, Ximing; and many others.

The gate to the compound of the cloistered abbot

But what caught my attention more than anything was this: I was "introduced" to a monk--the abbot, I think--who was living in seclusion behind a gate sealed off with tape (cleverly marked "seal"). Inside, I gather, was a courtyard and the hall where he lived; the nuns passed him his food under the gate. I don't have enough Chinese to really understand what was going on: was he undertaking religious discipline? Was this to prove to all and sundry that he was living celibate, away from the nuns? A sign in Chinese says, "Quiet area for chanting the Buddha's name: Do not enter," so I lean toward the "religious discipline" explanation, but I just wish I had more details.

Indulge me here as I tell you that I, too, once tried to take this temple's name, meaning "Western Brightness," as my own, along with "Bo," which sounds a little like the first syllable of my family name. So I would have been Bo Ximing. Just about when I was ready to make the change, a scandal broke featuring a man named Bo Xilai, who had brothers named Bo Xiyong, Bo Xicheng, and Bo Xining. I decided to abort!

Seat of the Master's Master: Daxingshan Temple

Daxingshan (Great Propagation of Goodness) Temple stands outside and to the west of Xi'an's south gate. You could take Ximing Temple and our final destination, Qinglong, and fit them into Daxingshan Temple with room to spare. But the temple is significant in our story only because here lived the monk Amoghavajra (705-774, called Bukong or "Not in Vain" in Chinese). Also a translator, he was born in Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan of an Indian father and Sogdian (a sort of Persian) mother. Small wonder he became a translator!

A statue of Kukai at Daxingshan Temple

Amoghavajra was a teacher of esoteric Buddhism, and is considered the Fourth Patriarch of a lineage in which the great Indian monk Nagarjuna was the First and Kukai was the Eighth. Thus his importance to Kukai's story. His student Shubhakarasimha (another Indian in China) passed the teaching to his student Yixing, and he passed it to a monk we'll meet in a moment.

This pagoda holds the remains of the esoteric patriarch Amoghavajra (Bukong)

Daxingshan Temple is immense and fascinating. Amoghavajra's memorial pagoda still stands on the grounds, and there's also a large outdoor statue of Konghai. Some of the other features include halls containing images of the torments of hell, the life of the Buddha, and various incarnations of Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

The Site of Transmission: Qinglong Temple

Qinglong ("Blue Dragon") Temple is the one to which I snuck away during my 2007 "business" trip. My, what a difference on my visit in 2010! A huge Tang-style gate had been built out front (kids were using the giant studs on it as a rock-climbing wall), and a huge structure--marked as a museum on Google Maps today--was being built between that gate and the main road.

A mammoth new gate in Ye Olde Tang style was added between my visits in 2007 and 2010. I’m sure the place has changed a lot since.

But the grounds inside remained pleasantly sleepy (though I'm sure I'd barely recognize them today, with the recent development). Most of what I saw was (again!) built by Japanese devotees, starting in 1981. Unlike the exile of Ximing Temple to the hinterlands, however, today's Qinglong is essentially where it's always been.

The memorial to Kukai on my visit in January 2007. The five-stone gorinto on top is from Japan.

The temple as I saw it was divided into three adjoining compounds arranged east-to-west. Entering by the east gate, you see a monument to Kukai, dedicated in 1982. The five stones at the top, in the shape of a gorinto or five-level miniature pagoda, is said to have come from Japan.

This monument to World Peace is also in the east compound. Guanyin (Avalokiteshvara) is on the left; Kukai is on the right; Kukai's (and my) favorite Buddha, Mahavairochana, is in the center; and a new building is going up outside.

Next, the central compound has a tall building called the Cloud Peak Pavilion, surrounded by gardens and walkways. The grounds are said to be an excellent place for viewing cherry blossoms, but I've never been there in season.

The Huiguo Konghai Memorial Hall; stones marking the original Main Hall are visible near either side of the lawn.

Finally, on the west, is the reconstructed Main Hall, with the foundations of the original in a grassy area in front of it. It's called the Huiguo Konghai Memorial Hall. Konghai, again, is the Chinese pronunciation of Kukai, but what or who is Huiguo? He is none other than the student of Yixing and the teacher of Kukai, thus the Seventh of the Eight Great Doctrine-Expounding Patriarchs of Shingon Buddhism. Statues of Huiguo and Kukai, with a Buddhist triad between them, adorn the main altar. Around the hall are various memorabilia of the two great masters, and of Sino-Japanese relations.

The story is often told: Kukai had expected to spend twenty years studying in China. When he met Huiguo at Qinglong Temple, the 60-year-old Patriarch looked on him and exclaimed immediately, "I knew that you would come! I have waited for such a long time! ... My life is drawing to an end, and until you came there was no one to whom I could transmit the teachings." He then gave Kukai instructions on how to prepare for his primary initiation.

The altar in the Main Hall features statues of Kukai and his master, Huiguo.

Huiguo described teaching Kukai as like "pouring water from one jar into another." In less than a year, Kukai was ready to become the Eighth Patriarch, and Huiguo's final words to him ended with: "Your task is to transmit [these teachings] to the Eastern Land [Japan.] Do your best! Do your best!" Not long afterward, Huiguo passed away.

--------

There is so much more to tell, like how Kukai studied Sanskrit in China, and either himself or through his students thus contributed to the creation of the Japanese syllabary, an alternative to the Chinese characters called kanji. Traveling the thousand miles or so to and from the coast, Kukai must have stayed in dozens of temples--but I can't find a list (though I'm pretty sure the temple I lived in in Yangzhou claimed "Kukai slept here"). I'm sure we'll visit this pivotal character again.

Until next time, may you and your loved ones and all sentient beings be well and happy.

Adios, Amigos!

Listen to the audio version of this post at Archive.org.

If you have any problems reading the Newsletter or accessing the Podcast, please write to me at TheTempleGuy@GMail.com, and I'll help you in any way I can!

In the next episode: Come along as I revisit the temple I knew better than any other in Japan, the Hase Kannon at Kamakura.